Here are some stem cell stories that caught our eye this past week. Some are groundbreaking science, others are of personal interest to us, and still others are just fun.

Stem cells may be option in glaucoma. A few (potentially) blind mice did not run fast enough in an Iowa lab. But lucky for them they did not run into a farmer’s wife wielding a knife. Instead they had their eye sight saved by a team at the University of Iowa that corrected the plumbing in the back of their eyes with stem cells. They had a rodent version of glaucoma, which allows fluid to build up in the eye causing pressure that eventually damages the optic nerve and leads to blindness.

The fluid buildup results from a breakdown of the trabecular meshwork, a patch of cells that drains fluid from the eye. The Iowa researchers repaired that highly valuable patch with cells grown from iPS type stem cells created by reprogramming adult cells into an embryonic-like state. The trick with any early stage stem cell is getting it to mature into the desired tissue. This team pulled that off by growing the cells in a culture dish that had previously housed trabecular meshwork cells, which must have left behind some chemical signals that directed the growth of the stem cells.

The cells restored proper drainage in the mice. Also notable, the cells not only acted to replace damaged tissue directly, but they also seem to have summoned the eye’s own healing powers to do more repair. The research team also worked at the university affiliated Veterans Affairs Hospital, and the VA system issued a press release on the work published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of sciences, which was posted by Science Codex.

A “mini-brain” from a key area. The brain is far from a uniform organ. Its many distinct divisions have very different functions. A few research teams have succeeded in coaxing stem cells into forming multi-layered clumps of cells referred to as “brain organoids” that mimic some brain activity, but those have generally been parts of the brain near the surface responsible for speech, learning and memory. Now a team in Singapore has created an organoid that shows activity of the mid-brain, that deep central highway for signals key to vision, hearing and movement.

The midbrain houses the dopamine nerves damaged or lost in Parkinson’s disease, so the mini-brains in lab dishes become immediate candidates for studying potential therapies and they are likely to provide more accurate results than current animal models.

“Considering one of the biggest challenges we face in PD research is the lack of accessibility to the human brains, we have achieved a significant step forward. The midbrain organoids display great potential in replacing animals’ brains which are currently used in research,” said Ng Huck Hui of A*Star’s Genome Institute of Singapore where the research was conducted in a press release posted by Nanowerk.

The website Mashable had a reporter at the press conference in Singapore when the institute announce the publication of the research in Cell Stem Cell. They have some nice photos of the organoids as well as a microscopic image showing the cells containing a black pigment typical of midbrain cells, one of the bits of proof the team needed to show they created what they wanted.

Stem cell clinical trials listings. Not a day goes by that I, or one of my colleagues, do not refer a desperate patient or family member—often several per day—to the web site clinicaltrials.gov. We do it with a bit of unease and usually some caveats but it is the only resource out there providing any kind of searchable listing of clinical trials. Not everything listed at this site maintained by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) is a great clinical trial. NIH maintains the site, and sets certain baseline criteria to be listed, but the agency does not vet postings.

Over the past year a new controversy has cropped up at the site. A number of for profit clinics have registered trials that require patients to pay many thousands of dollars for the experimental stem cell procedure. Generally, in clinical trials, participation is free for patients. Kaiser Health News, an independent news wire supported by the Kaiser Family Foundation distributed a story this week on the phenomenon that was picked up by a few outlets including the Washington Post. But the version with the best links to added information ran in Stat, an online health industry portal developed by The Boston Globe, which has become one of my favorite morning reads.

The story leads with an anecdote about Linda Smith who went to the trials site to look for stem cell therapies for her arthritic knees. She found a listing from StemGenex and called the listed contact only to find out she would first have to pay $14,000 for the experimental treatment. The company told the author that they are not charging for participation in the posted clinical trial because it only covers the observation phase after the therapy, not the procedure itself. The reporter found multiple critics who suggested the company was splitting hairs a bit too finely with that explanation.

But the NIH came in for just as much criticism for allowing those trials to be listed at all. The web site already requires organizations listing trials to disclose information about the committees that oversee the safety of the patients in the trial, and critics said they should also demand disclosure of payment requirements, or outright ban such trials from the site.

“The average patient and even people in health care … kind of let their guard down when they’re in that database. It’s like, ‘If a trial is listed here, it must be OK,’” said Paul Knoepfler, a CIRM grantee and fellow blogger at the University of California, Davis. “Most people don’t realize that creeping into that database are some trials whose main goal is to generate profit.”

The NIH representative quoted in the article made it sound like the agency was open to making some changes. But no promises were made.

Added note 7/30. While this post factually describes an article that appeared in the mainstream media, the role of this column, I should add that while I did not take a position on paid trials, I am thrilled Stemgenex is collecting data and look forward to them sharing that data in a timely, peer-reviewed fashion.

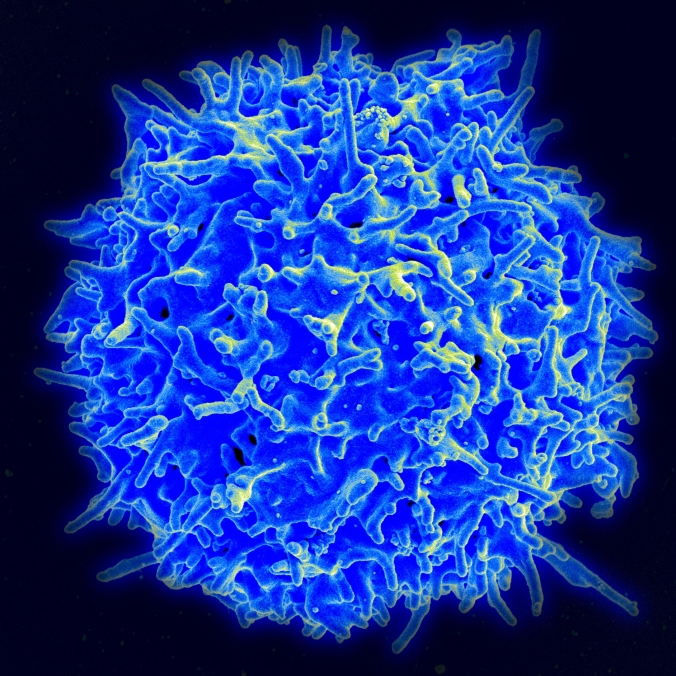

Off the shelf T cells. We at CIRM got some good news this week. We always like it when we see an announcement that technology from a researcher we have supported gets licensed to a company. That commercialization moves it a giant step closer to helping patients.

This week, Kite Pharma licensed a system developed in the lab of Gay Crooks at the University of California, Los Angeles, that creates an artificial thymus “organoid” in a dish capable of mass producing the immune system’s T cells from pluripotent stem cells. Just growing stem cells in the lab yields tiny amounts of T cells. They naturally mature in our bodies in the thymus gland, and seem to need that nurturing to thrive.

T-cell based immune therapy is all the rage now in cancer therapy because early trials are producing some pretty amazing results, and Kite is a leader in the field. But up until now those therapies have all been autologous—they used the patient’s own cells and manipulate them individually in the lab. That makes for a very expensive therapy. Kite sees the Crooks technology as a way to turn the procedure into an allogeneic one—using donor cells that could be pre-made for an “off-the-shelf” therapy. Their press release also envisioned adding some genetic manipulation to make the cells less likely to cause immune complications.

FierceBiotech published a bit more analysis of the deal, but we are not going to go into more detail on the actual science now. Crooks is finalizing publication of the work in a scientific journal, and when she does you can get the details here. Stay tuned.