Welcome to our “Throwback Thursday” series on the Stem Cellar. Over the years, we’ve accumulated an arsenal of exciting stem cell stories about advances towards stem cell-based cures for serious diseases. Today we’re featuring stories about the progress of CIRM-funded research and clinical trials that are aimed at developing stem cell-based treatments for HIV/AIDS.

Tomorrow, December 1st, is World AIDS Day. In honor of the 34 million people worldwide who are currently living with HIV, we’re dedicating our latest #ThrowbackThursday blog to the stem cell research and clinical trials our Agency is funding for HIV/AIDS.

To jog your memory, HIV is a virus that hijacks your immune cells. If left untreated, HIV can lead to AIDS – a condition where your immune system is compromised and cannot defend your body against infection and diseases like cancer. If you want to read more background about HIV/AIDs, check out our disease fact sheet.

To jog your memory, HIV is a virus that hijacks your immune cells. If left untreated, HIV can lead to AIDS – a condition where your immune system is compromised and cannot defend your body against infection and diseases like cancer. If you want to read more background about HIV/AIDs, check out our disease fact sheet.

Stem Cell Advancements in HIV/AIDS

While patients can now manage HIV/AIDS by taking antiretroviral therapies (called HAART), these treatments only slow the progression of the disease. There is no effective cure for HIV/AIDS, making it a significant unmet medical need in the patient community.

CIRM is funding early stage research and clinical stage research projects that are developing cell based therapies to treat and hopefully one day cure people of HIV. So far, our Agency has awarded 17 grants totalling $72.9 million in funding to HIV/AIDS research. Below is a brief description of four of these exciting projects:

Discovery Stage Research

Dr. David Baltimore at the California Institute of Technology is developing an innovative stem cell-based immunotherapy that would prevent HIV infection in specific patient populations. He recently received a CIRM Quest award, (a funding initiative in our Discovery Stage Research Program) to pursue this research.

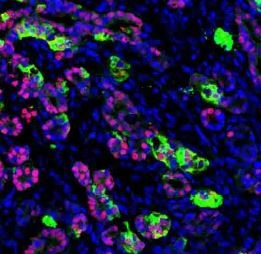

CIRM science officer, Dr. Ross Okamura, oversees Baltimore’s CIRM grant. He explained how the Baltimore team is genetically modifying the blood stem cells of patients so that they develop into immune cells (called T cells) that specifically recognize and target the HIV virus.

Ross Okamura, PhD

“The approach Dr. Baltimore is taking in his CIRM Discovery Quest award is to engineer human immune stem cells to suppress HIV infection. He is providing his engineered cells with T cell protein receptors that specifically target HIV and then exploring if he can reduce the viral load of HIV (the amount of virus in a specific volume) in an animal model of the human immune system. If successful, the approach could provide life-long protection from HIV infection.”

While Baltimore’s team is currently testing this strategy in mice, if all goes well, their goal is to translate this strategy into a preventative HIV therapy for people.

Clinical Trials

CIRM is currently funding three clinical trials focused on HIV/AIDS led by teams at Calimmune, City of Hope/Sangamo Biosciences and UC Davis. Rather than spelling out the details of each trial, I’ll refer you to our new Clinical Trial Dashboard (a screenshot of the dashboard is below) and to our new Blood & Immune Disorders clinical trial infographic we released in October.

As you can see from these projects, CIRM is committed to funding cutting edge research in HIV/AIDS. We hope that in the next few years, some of these projects will bear fruit and help advance stem cell-based therapies to patients suffering from this disease.

I’ll leave you with a few links to other #WorldAIDSDay relevant blogs from our Stem Cellar archive and our videos that are worth checking out.

- Key Steps Along the Way to Finding Treatments for HIV on World AIDS Day (12.1.16)

- HIV/AIDS: Progress and Promise of Stem Cell Research (12.24.15)

- Stem Cells deliver genes to make T cells resistant to HIV (6.2.15)

- CIRM videos about HIV/AIDS research