For more than 20 years Dr. Benoit Bruneau has been trying to identify the causes of congenital heart disease, the most common form of birth defect in the U.S. It turns out that it’s not one cause, but many.

Congenital heart disease covers a broad range of defects, some relatively minor and others life-threatening and even fatal. It’s been known that a mutation in a gene called TBX5 is responsible for some of these defects, so, in a CIRM-funded study ($1.56 million), Bruneau zeroed in on this mutation to see if it could help provide some answers.

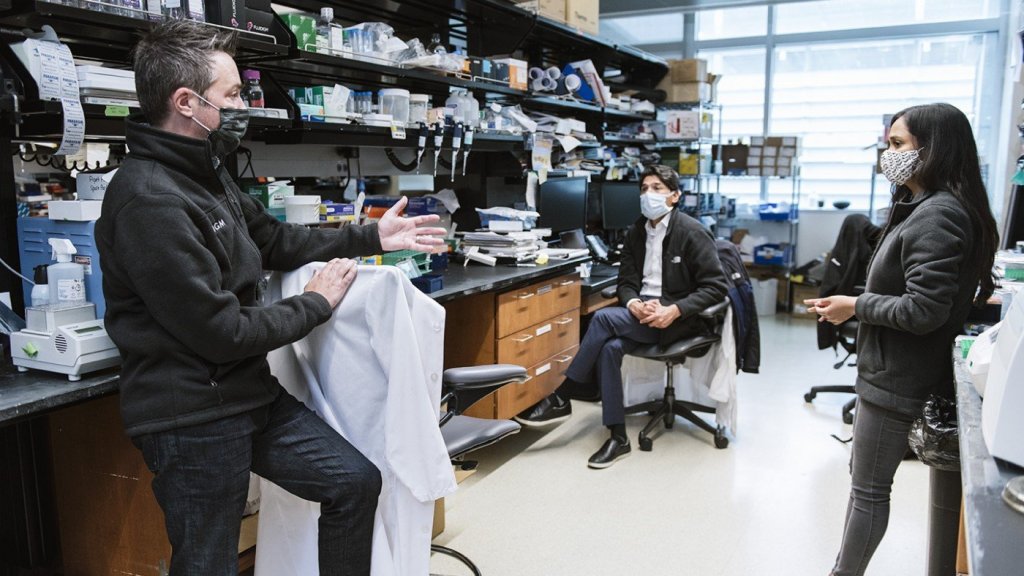

In the past Bruneau, the director of the Gladstone Institute of Cardiovascular Disease, had worked with a mouse model of TBX5, but this time he used human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). These are cells that can be manipulated in the lab to become any kind of cell in the human body. In a news release Bruneau says this was an important step forward.

“This is really the first time we’ve been able to study this genetic mutation in a human context. The mouse heart is a good proxy for the human heart, but it’s not exactly the same, so it’s important to be able to carry out these experiments in human cells.”

The team took some iPSCs, changed them into heart cells, and used a gene editing tool called CRISPR-Cas9 to create the kinds of mutations in TBX5 that are seen in people with congenital heart disease. What they found was some genes were affected a lot, some not so much. Which is what you might expect in a condition that causes so many different forms of problems.

“It makes sense that some are more affected than others, but this is the first experimental data in human cells to show that diversity,” says Bruneau.

But they didn’t stop there. Oh no. Then they did a deep dive analysis to understand how the different ways that different cells were impacted related to each other. They found some cells were directly affected by the TBX5 mutation but others were indirectly affected.

The study doesn’t point to a simple way of treating congenital heart disease but Bruneau says it does give us a much better understanding of what’s going wrong, and perhaps will give us better ideas on how to stop that.

“Our new data reveal that the genes are really all part of one network—complex but singular—which needs to stay balanced during heart development. That means if we can figure out a balancing factor that keeps this network functioning, we might be able to help prevent congenital heart defects.”

The study is published in the journal Developmental Cell.