Stem cells…eh, who needs them anyway?!

That’s what you might be thinking after today, at least for some forms of liver disease. That’s because a team of researchers from UCSF and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center just published results in Nature showing liver cells can directly change identity, or transdifferentiate, in order to build, from scratch, structures missing due to disease.

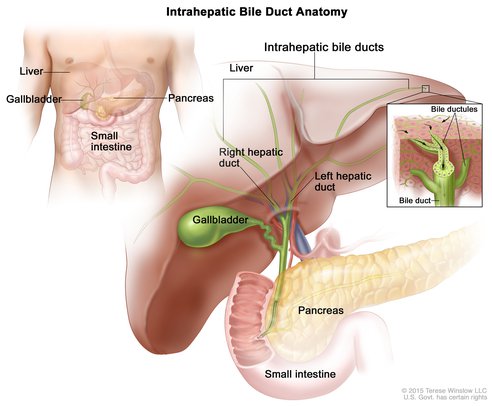

The liver contains a network of tubes called bile ducts that carry fat-digesting bile to the small intestine via the gallbladder.

Image: National Cancer Inst.

The extraordinary regenerative power of the liver in animals is well-documented. A human liver, for instance, can fully regrow from just 25% of its original mass. That’s thanks to the hepatocyte, the main type of liver cell, that has the ability to replenish pre-existing tissue lost due to disease or injury. What hasn’t been as clear cut, is whether the hepatocyte has the capacity to change identity and build functional liver structures from scratch that never developed in the first place due to genetic disorders.

To examine that possibility, the study – funded in part by CIRM – focused on an inherited liver disease called Alagille syndrome which is caused by abnormal bile ducts. Produced by the liver, bile helps digest fats in our diet. It travels from the liver via bile ducts – tree branch-like tube structures in the liver – to the gallbladder, where it’s stored before moving on to the small intestine. In Alagille syndrome, the bile ducts are fewer in number, narrower in size or altogether missing. As a result, the bile builds up in the liver causing scarring and severe damage. Nearly half of all those with Alagille syndrome, require a liver transplant, usually in childhood.

The research team mimicked the symptoms of Alagille syndrome in mice by genetically engineering the animals to lack cholangiocytes, the cells that form bile ducts. Sure enough, liver damage from bile buildup was observed in these mice at birth due to the missing bile duct structures, also called the biliary tree. However, 90% of the mice survived and eventually formed a functional biliary tree. The team went on to show, for the first time, that the hepatocytes had converted en masse into cholangiocytes and created the wholly new bile ducts.

Mice that mimic Alagille syndrome are born without the branches of the biliary tree, an important “plumbing system” in the liver (A), but show a near-normal biliary system as adults (B). To build the missing branches, liver cells switch identity and form tubes, shown in green, that connect to the trunk of the biliary tree, shown in blue (C). Image: Cincinnati Children’s

The underlying molecular mechanisms of this process were further examined. The researchers showed that the lack of a particular gene activity pathway due to the absence of cholangiocytes during development causes a replacement pathway, stimulated by a protein called TGF-beta, to kick into gear. As a result, the hepatocytes convert into cholangiocytes and form bile ducts. To make a direct connection with the human form of the disease, the researchers found evidence that TGF-beta is active in the liver samples of some patients but not in the livers from healthy individuals.

With this Alagille syndrome mouse model in hand, the researchers want to identify which transcription factors – proteins that bind DNA and regulate gene activity – are involved in changing the liver cells into bile duct cells. Holger Willenbring, MD, PhD, a senior author and CIRM grantee, explained the rationale behind this approach in a press release:

Holger Willenbring

“Using transcription factors to make bile ducts from hepatocytes has potential as a safe and effective therapy. With our finding that an entire biliary system can be ‘retrofitted’ in the mouse liver, I am encouraged that this eventually will work in patients.”

So rather than developing a stem cell-based therapy in the lab which is then transplanted into a patient, this approach would rely on stimulating the regenerative capacity of liver cells that are already inside the body. And if it eventually works in patients with Alagille syndrome, which only affects 1 in 30,000, it’s possible it could be applied to other liver diseases as well.