Short telomeres associated with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy.

Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD) is a severe muscle wasting disease that typically affects young men. There is no cure for DMD and the average life expectancy is 26. These are troubling facts that scientists at the University of Pennsylvania are hoping to change with their recent findings in Stem Cell Reports.

The team discovered that the muscle stem cells in DMD patients have shortened telomeres, which are the protective caps on the ends of chromosomes that prevent the loss of precious genetic information during cell division. Each time a cell divides, a small section of telomere is lost. This typically isn’t a problem because telomeres are long enough to protect cells through many divisions.

But it turns out this is not the case for the telomeres in the muscle stem cells of DMD patients. Because DMD patients have weak muscles, they experience constant muscle damage and their muscle stem cells have to divide more frequently (basically non-stop) to repair and replace muscle tissue. This is bad news for the telomeres in their muscle stem cells. Foteini Mourkioti, senior author on the study, explained in a news release,

“We found that in boys with DMD, the telomeres are so short that the muscle stem cells are probably exhausted. Due to the DMD, their muscle stem cells are constantly repairing themselves, which means the telomeres are getting shorter at an accelerated rate, much earlier in life. Future therapies that prevent telomere loss and keep muscle stem cells viable might be able to slow the progress of disease and boost muscle regeneration in the patients.”

With these new insights, Mourkioti and his team believe that targeting muscle stem cells before their telomeres become too short is a good path to pursue for developing new treatments for DMD.

“We are now looking for signaling pathways that affect telomere length in muscle stem cells, so that in principle we can develop drugs to block those pathways and maintain telomere length.”

Making Motor Neurons from Skin.

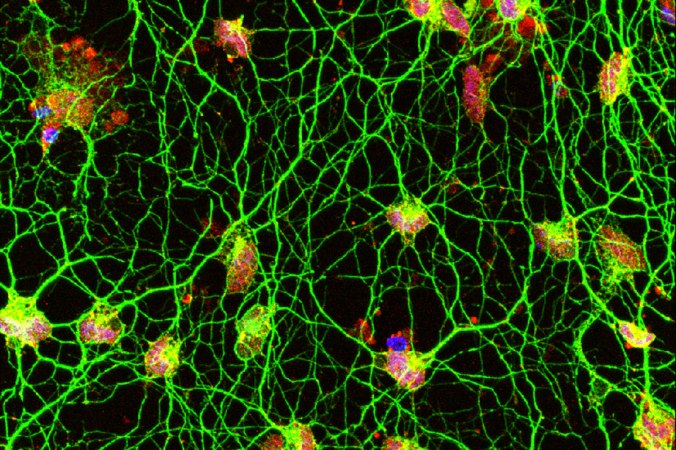

Skin cells and brain cells are like apples and oranges, they look completely different and have different functions. However, in the past decade, researchers have developed methods to transform skin cells into neurons to study neurodegenerative disorders and develop new strategies to treat brain diseases.

Scientists at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis published new findings on this topic yesterday in the journal Cell Stem Cell. In a nut shell, the team discovered that a specific combination of microRNAs (molecules involved in regulating what genes are turned on and off) and transcription factors (proteins that also regulate gene expression) can turn human skin cells into motor neurons, which are the brain cells that degenerate in neurodegenerative diseases like ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease.

This magical cocktail of factors told the skin cells to turn off genes that make them skin and turn on genes that transformed them into motor neurons. The scientists used skin cells from healthy individuals but will soon use their method to make motor neurons from patients with ALS and other motor neuron diseases. They are also interested in generating neurons from older patients who are more advanced in their disease. Andrew Yoo, senior author on the study, explained in a news release,

“In this study, we only used skin cells from healthy adults ranging in age from early 20s to late 60s. Our research revealed how small RNA molecules can work with other cell signals called transcription factors to generate specific types of neurons, in this case motor neurons. In the future, we would like to study skin cells from patients with disorders of motor neurons. Our conversion process should model late-onset aspects of the disease using neurons derived from patients with the condition.”

This research will make it easier for other scientists to grow human motor neurons in the lab to model brain diseases and potentially develop new treatments. However, this is still early stage research and more work should be done to determine whether these transformed motor neurons are the “real deal”. A similar conclusion was shared by Julia Evangelou Strait, the author of the Washington University School of Medicine news release,

“The converted motor neurons compared favorably to normal mouse motor neurons, in terms of the genes that are turned on and off and how they function. But the scientists can’t be certain these cells are perfect matches for native human motor neurons since it’s difficult to obtain samples of cultured motor neurons from adult individuals. Future work studying neuron samples donated from patients after death is required to determine how precisely these cells mimic native human motor neurons.”

Students Today, Scientists Tomorrow.

What did you want to be when you were growing up? For Benjamin Nittayo, a senior at Cal State University Los Angeles, it was being a scientist researching a cure for acute myeloid leukemia (AML), a form of blood cancer that took his father’s life. Nittayo is making his dream into a reality by participating in a summer research internship through the Eugene and Ruth Roberts Summer Student Academy at the City of Hope in Duarte California.

Nittayo has spent the past two summers doing cancer research with scientists at the Beckman Research Institute at City of Hope and hopes to get a PhD in immunology to pursue his dream of curing AML. He explained in a City of Hope news release,

“I want to carry his memory on through my work. Being in this summer student program helped me do that. It influenced the kind of research I want to get into as a scientist and it connected me to my dad. I want to continue the research I was able to start here so other people won’t have to go through what I went through. I don’t wish that on anybody.”

The Roberts Academy also hosts high school students who are interested in getting their first experience working in a lab. Some of these students are part of CIRM’s high school educational program Summer Program to Accelerate Regenerative Medicine Knowledge or SPARK. The goal of SPARK is to train the next generation of stem cell scientists in California by giving them hands-on training in stem cell research at leading institutes in the state.

This year, the City of Hope hosted the Annual SPARK meeting where students from the seven different SPARK programs presented their summer research and learned about advances in stem cell therapies from City of Hope scientists.

Ashley Anderson, a student at Mira Costa High School in Manhattan Beach, had the honor of giving the City of Hope SPARK student talk. She shared her work on Canavan’s disease, a progressive genetic disorder that damages the brain’s nerve cells during infancy and can cause problems with movement and muscle weakness.

Ashley Anderson, a student at Mira Costa High School in Manhattan Beach, had the honor of giving the City of Hope SPARK student talk. She shared her work on Canavan’s disease, a progressive genetic disorder that damages the brain’s nerve cells during infancy and can cause problems with movement and muscle weakness.

Under the guidance of her mentor Yanhong Shi, Ph.D., who is a Professor of Developmental and Stem Cell Biology at City of Hope, Ashley used induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) from patients with Canavan’s to generate different types of brain cells affected by the disease. Ashley helped develop a protocol to make large quantities of neural progenitor cells from these iPSCs which the lab hopes to eventually use in clinical trials to treat Canavan patients.

Ashley has always been intrigued by science, but thanks to SPARK and the Roberts Academy, she was finally able to gain actual experience doing science.

“I was looking for an internship in biosciences where I could apply my interest in science more hands-on. Science is more than reading a textbook, you need to practice it. That’s what SPARK has done for me. Being at City of Hope and being a part of SPARK was amazing. I learned so much from Dr. Shi. It’s great to physically be in a lab and make things happen.”

You can read more about Ashley’s research and those of other City of Hope SPARK students here. You can also find out more about the educational programs we fund on our website and on our blog (here and here).