A dying cell’s last breath triggers stem cell division. Most cells in your body are in a constant state of turnover. The cells of your lungs, for instance, replace themselves every 2 to 3 weeks and, believe it or not, you get a new intestine every 2 to 3 days. We can thank adult stem cells residing in these organs for producing the new replacement cells. But with this continual flux, how do the stem cells manage to generate just the right number of cells to maintain the same organ size? Just a slight imbalance would lead to either too few cells or too many which can lead to organ dysfunction and disease.

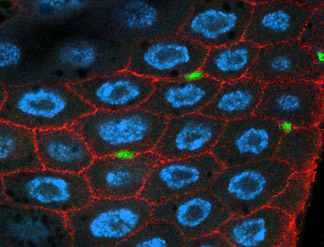

The intestine turnovers every five days. Stem cells (green) in the fruit fly intestine maintain organ size and structure. Image: Lucy Erin O’Brien/Stanford U.

Stanford University researchers published results on Friday in Nature that make inroads into explaining this fascinating, fundamental question about stem cell and developmental biology. Studying the cell turnover process of the intestine in fruit flies, the scientists discovered that, as if speaking its final words, a dying intestinal cell, or enterocyte, directly communicates with an intestinal stem cell to trigger it to divide and provide young, healthy enterocytes.

To reach this conclusion, the team first analyzed young enterocytes and showed that a protein these cells produce, called E-cadherin, blocks the release of a growth factor called EGF, a known stimulator of cell division. When young enterocytes became old and begin a process called programmed cell death, or apoptosis, the E-cadherin levels drop which removes the inhibition of EGF. As a result, a nearby stem cell now receives the EGF’s cell division signal, triggering it to divide and replace the dying cell. In her summary of this research in Stanford’s Scope blog, science writer Krista Conger explains how the dying cell’s signal to a stem cell ensures that there no net gain or loss of intestinal cells:

“The signal emitted by the dying cell travels only a short distance to activate only nearby stem cells. This prevents an across-the-board response by multiple stem cells that could result in an unwanted increase in the number of newly generated replacement cells.”

Because E-cadherin and the EGF receptor (EGFR) are each associated with certain cancers, senior author Lucy Erin O’Brien ponders the idea that her lab’s new findings may explain an underlying mechanism of tumor growth:

Lucy Erin O’Brien Image: Stanford U.

“Intriguingly, E-cadherin and EGFR are each individually implicated in particular cancers. Could they actually be cooperating to promote tumor development through some dysfunctional version of the normal renewal mechanism that we’ve uncovered?”

How a videogame could make gene editing safer (Kevin McCormack). The gene editing tool CRISPR has been getting a lot of attention this past year, and for good reason, it has the potential to eliminate genetic mutations that are responsible for some deadly diseases. But there are still many questions about the safety of CRISPR, such as how to control where it edits the genome and ensure it doesn’t cause unexpected problems.

Now a team at Stanford University is hoping to use a videogame to find answers to some of those questions. Here’s a video about their project:

The team is using the online game Eterna – which describes itself as “Empowering citizen scientists to invent medicine”. In the game, “players” can build RNA molecules that can then be used to turn on or off specific genes associated with specific diseases.

The Stanford team want “players” to design an RNA molecule that can be used as an On/Off switch for CRISPR. This would enable scientists to turn CRISPR on when they want it, but off when it is not needed.

In an article on the Stanford News website, team leader Howard Chang said this is a way to engage the wider scientific community in coming up with a solution:

“Great ideas can come from anywhere, so this is also an experiment in the democratization of science. A lot of people have hidden talents that they don’t even know about. This could be their calling. Maybe there’s somebody out there who is a security guard and a fantastic RNA biochemist, and they don’t even know it. The Eterna game is a powerful way to engage lots and lots of people. They’re not just passive users of information but actually involved in the process.”

They hope up to 100,000 people will play the game and help find a solution.

Altered stem cell gene activity partly to blame for obesity. People who are obese are often ridiculed for their weight problems because their condition is chalked up to a lack of discipline or self-control. But there are underlying biological processes that play a key role in controlling body weight which are independent of someone’s personality. It’s known that so-called satiety hormones – which are responsible for giving us the sensation that we’re full from a meal – are reduced in obese individuals compared to those with a normal weight.

Stem cells may have helped Al Roker’s dramatic weight loss after bariatric surgery. Photo: alroker.com

Bariatric surgery, which reduces the size of the stomach, is a popular treatment option for obesity and can lead to remarkable weight loss. Al Roker, the weatherman for NBC’s Today Show is one example that comes to mind of a weight loss success story after having this procedure. It turns out that the weight loss is not just due to having a smaller stomach and in turn smaller meals, but researchers have shown that the surgery also restores the levels of satiety hormones. So post-surgery, those individuals get a more normal, “I’m full”, feedback from their brains after eating a meal.

A team of Swiss doctors wanted to understand why the satiety hormone levels return to normal after bariatric surgery and this week they reported their answer in Scientific Reports. They analyzed enteroendocrine cells – the cells that release satiety hormones into the bloodstream and to the brain in response to food that enters the stomach and intestines – in obese individuals before and after bariatric surgery as well as a group of people with normal weight. The results showed that obese individuals have fewer enteroendocrine cells compared with the normal weight group. Post-surgery, those cells return to normal levels.

Cells which can release satiety hormones are marked in green. For obese patients (middle), the number of these cells is markedly lower than for lean people (top) and for overweight patients three months after surgery (bottom). Image: University of Basil.

A deeper examination of the cells from the obese study group revealed altered patterns of gene activity in stem cells that are responsible for generating the enteroendocrine cells. In the post-surgery group, the patterns of gene activity, as seen in the normal weight group, are re-established. As mentioned in a University of Basil press release, these results stress that obesity is more than just a problem of diet and life-style choices:

“There is no doubt that metabolic factors are playing an important part. The study shows that there are structural differences between lean and obese people, which can explain lack of satiation in the obese.”