Stem cell research is advancing so fast that it’s sometimes hard to keep up. That’s one of the reasons we have our Friday roundup, to let you know about some fascinating research that came across our desk during the week that you might otherwise have missed.

Of course, another way to keep up with the latest in stem cell research is to join us for our free Patient Advocate Event at UC San Diego next Thursday, April 20th from 12-1pm. We are going to talk about the progress being made in stem cell research, the problems we still face and need help in overcoming, and the prospects for the future.

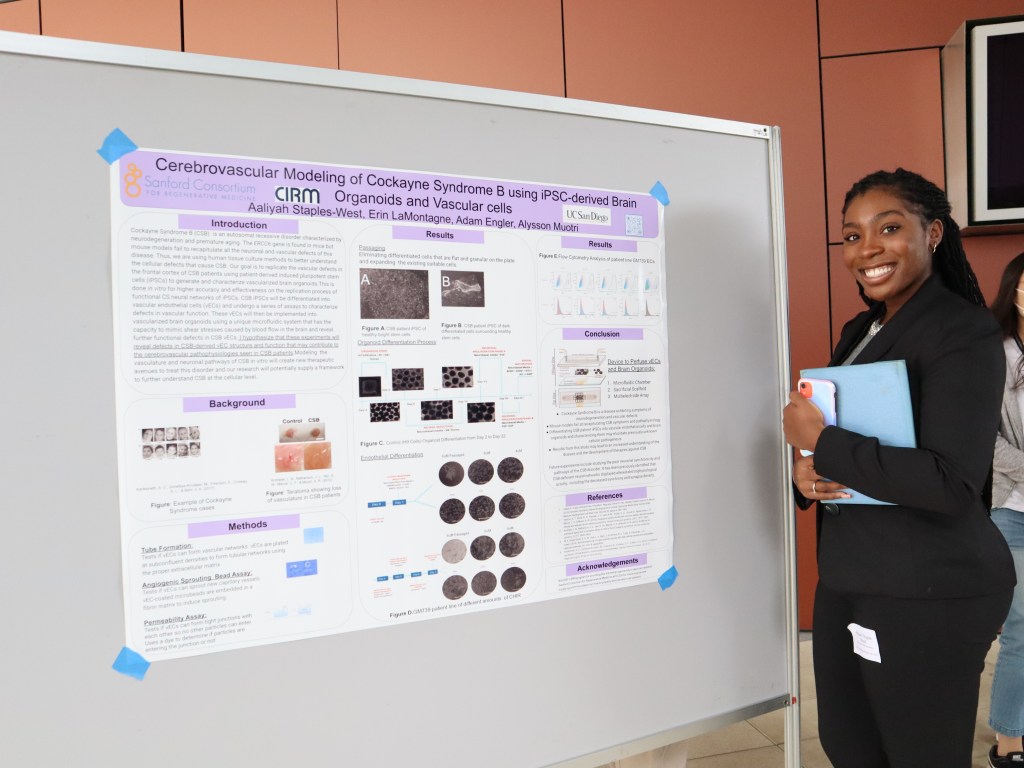

We have four great speakers:

- Catriona Jamieson, Director of the CIRM UC San Diego Alpha Stem Cell Clinic and an expert on cancers of the blood

- Jonathan Thomas, PhD, JD, Chair of CIRM’s Board

- Jennifer Briggs Braswell, Executive Director of the Sanford Stem Cell Clinical Center

- David Higgins, Patient Advocate for Parkinson’s on the CIRM Board

We will give updates on the exciting work taking place at UCSD and the work that CIRM is funding. We have also set aside some time to get your thoughts on how we can improve the way we work and, of course, answer your questions.

What: Stem Cell Therapies and You: A Special Patient Advocate Event

When: Thursday, April 20th 12-1pm

Where: The Sanford Consortium for Regenerative Medicine, 2880 Torrey Pines Scenic Drive, La Jolla, CA 92037

Why: Because the people of California have a right to know how their money is helping change the face of regenerative medicine

Who: This event is FREE and open to everyone.

We have set up an EventBrite page for you to RSVP and let us know if you are coming. And, of course, feel free to share this with anyone you think might be interested.

This is the first of a series of similar Patient Advocate Update meetings we plan on holding around California this year. We’ll have news on other locations and dates shortly.

Fixing a mutation that causes muscular dystrophy (Karen Ring)

It’s easy to take things for granted. Take your muscles for instance. How often do you think about them? (Don’t answer this if you’re a body builder). Daily? Monthly? I honestly don’t think much about my muscles unless I’ve injured them or if they’re sore from working out.

Heart muscle cells (green) that don’t have dystrophin protein (Photo; UT Southwestern)

But there are people in this world who think about their muscles or their lack of them every day. They are patients with a muscle wasting disease called Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD). It’s the most common type of muscular dystrophy, and it affects mainly young boys – causing their muscles to progressively weaken to the point where they cannot walk or breathe on their own.

DMD is caused by mutations in the dystrophin gene. These mutations prevent muscle cells from making dystrophin protein, which is essential for maintaining muscle structure. Scientists are using gene editing technologies to find and fix these mutations in hopes of curing patients of DMD.

Last year, we blogged about a few of these studies where different teams of scientists corrected dystrophin mutations using CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing technology in human cells and in mice with DMD. One of these teams has recently followed up with a new study that builds upon these earlier findings.

Scientists from UT Southwestern are using an alternative form of the CRISPR gene editing complex to fix dystrophin mutations in both human cells and mice. This alternative CRISPR complex makes use of a different cutting enzyme, Cpf1, in place of the more traditionally used Cas9 protein. It’s a smaller protein that the scientists say can get into muscle cells more easily. Cpf1 also differs from Cas9 in what DNA nucleotide sequences it recognizes and latches onto, making it a new tool in the gene editing toolbox for scientists targeting DMD mutations.

Gene-edited heart muscle cells (green) that now express dystrophin protein (Photo: UT Southwestern)

Using CRISPR/Cpf1, the scientists corrected the most commonly found dystrophin mutation in human induced pluripotent stem cells derived from DMD patients. They matured these corrected stem cells into heart muscle cells in the lab and found that they expressed the dystrophin protein and functioned like normal heart cells in a dish. CRISPR/Cpf1 also corrected mutations in DMD mice, which rescued dystrophin expression in their muscle tissues and some of the muscle wasting symptoms caused by the disease.

Because the dystrophin gene is one of the longest genes in our genome, it has more locations where DMD-causing mutations could occur. The scientists behind this study believe that CRISPR/Cpf1 offers a more flexible tool for targeting different dystrophin mutations and could potentially be used to develop an effective gene therapy for DMD.

Senior author on the study, Dr. Eric Olson, provided this conclusion about their research in a news release by EurekAlert:

“CRISPR-Cpf1 gene-editing can be applied to a vast number of mutations in the dystrophin gene. Our goal is to permanently correct the underlying genetic causes of this terrible disease, and this research brings us closer to realizing that end.”

A cellular traffic jam is the culprit behind Huntington’s disease (Todd Dubnicoff)

Back in the 1983, the scientific community cheered the first ever mapping of a genetic disease to a specific area on a human chromosome which led to the isolation of the disease gene in 1993. That disease was Huntington’s, an inherited neurodegenerative disorder that typically strikes in a person’s thirties and leads to death about 10 to 15 years later. Because no effective therapy existed for the disease, this discovery of Huntingtin, as the gene was named, was seen as a critical step toward a better understand of Huntington’s and an eventual cure.

But flash forward to 2017 and researchers are still foggy on how mutations in the Huntingtin gene cause Huntington’s. New research, funded in part by CIRM, promises to clear some things up. The report, published this week in Neuron, establishes a connection between mutant Huntingtin and its impact on the transport of cell components between the nucleus and cytoplasm.

The pores in the nuclear envelope allows proteins and molecules to pass between a cell’s nucleus and it’s cytoplasm. Image: Blausen.com staff (2014).

To function smoothly, a cell must be able to transport proteins and molecules in and out of the nucleus through holes called nuclear pores. The research team – a collaboration of scientists from Johns Hopkins University, the University of Florida and UC Irvine – found that in nerve cells, the mutant Huntingtin protein clumps up and plays havoc on the nuclear pore structure which leads to cell death. The study was performed in fly and mouse models of HD, in human HD brain samples as well as HD patient nerve cells derived with the induced pluripotent stem cell technique – all with this same finding.

Huntington’s disease is caused by the loss of a nerve cells called medium spiny neurons. Image: Wikimedia commons

By artificially producing more of the proteins that make up the nuclear pores, the damaging effects caused by the mutant Huntingtin protein were reduced. Similar results were seen using drugs that help stabilize the nuclear pore structure. The implications of these results did not escape George Yohrling, a senior director at the Huntington’s Disease Society of America, who was not involved in the study. Yohrling told Baltimore Sun reporter Meredith Cohn:

“This is very exciting research because we didn’t know what mutant genes or proteins were doing in the body, and this points to new areas to target research. Scientists, biotech companies and pharmaceutical companies could capitalize on this and maybe develop therapies for this biological process”,

It’s important to temper that excitement with a reality check on how much work is still needed before the thought of clinical trials can begin. Researchers still don’t understand why the mutant protein only affects a specific type of nerve cells and it’s far from clear if these drugs would work or be safe to use in the context of the human brain.

Still, each new insight is one step in the march toward a cure.