THIS BLOG IS ALSO AVAILABLE AS AN AUDIO CAST

A team of researchers from Experimental and Clinical Research Center (ECRC) has introduced the gene editor CRISPR-Cas9 into human muscle stem cells for the first time using messenger RNA (mRNA), potentially discovering a method suitable for therapeutic applications.

The researchers are aiming to discover if this tool can repair mutations that lead to muscle atrophy in humans, and they are one step closer after finding that the method worked in mice suffering from the condition. But the method had a catch, ECRC researcher Helena Escobar says.

“We introduced the genetic instructions for the gene editor into the stem cells using plasmids – which are circular, double-stranded DNA molecules derived from bacteria.” But plasmids could unintentionally integrate into the genome of human cells, which is also double stranded, and then lead to undesirable effects that are difficult to assess. “That made this method unsuitable for treating patients,” Escobar says.

Getting mRNA Into Stem Cells

So the team set out to find a better alternative. They found it in the form of mRNA, a single-stranded RNA molecule that recently gained acclaim as a key component of two Covid-19 vaccines.

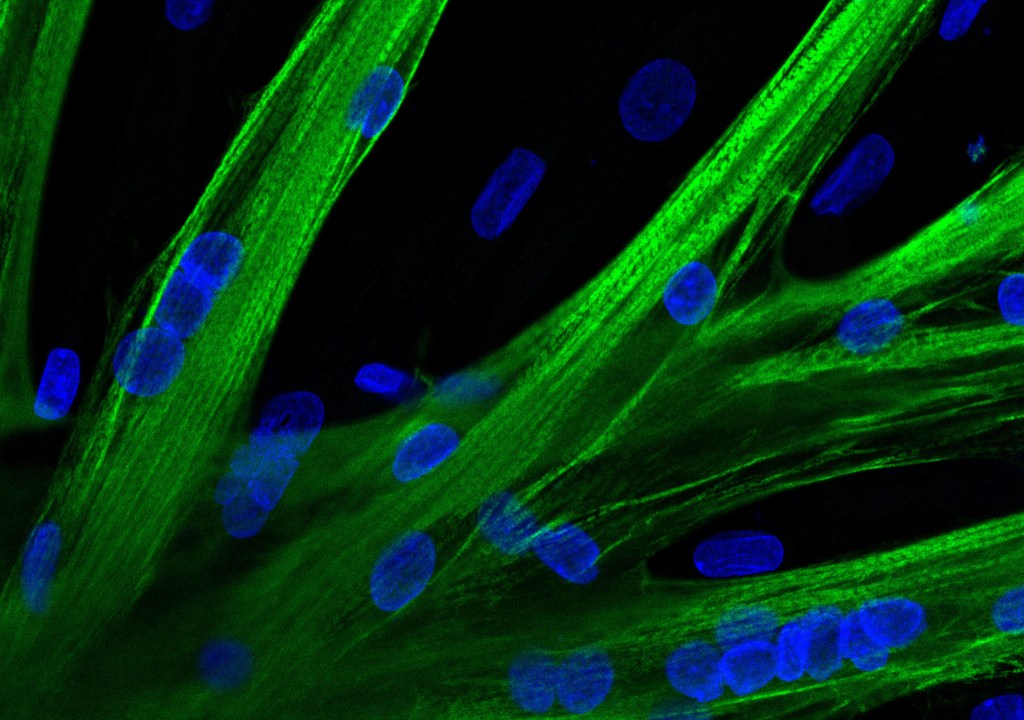

To get the mRNA into the stem cells, the researchers used a process called electroporation, which temporarily makes cell membranes more permeable to larger molecules. “With the help of mRNA containing the genetic information for a green fluorescent dye, we first demonstrated that the mRNA molecules entered almost all the stem cells,” explains Christian Stadelmann, a doctoral student at ECRC.

In the next step, the team used a deliberately altered molecule on the surface of human muscle stem cells to show that the method can be used to correct gene defects in a targeted manner.

Paving the Way for a Clinical Trial

Finally, the team tried out a tool similar to the CRISPR-Cas9 gene editor that does not cut the DNA, but only tweaks it at one spot with accuracy. In petri dish experiments, Stadelmann and his team were able to show that the corrected muscle stem cells are just as capable as healthy cells of fusing with each other and forming young muscle fibers.

Their latest paper, which is appearing in the journal Molecular Therapy Nucleic Acids, paves the way for a clinical trial for patients with hereditary muscle atrophy. The team expects to enroll five to seven patients toward the end of the year.

“Of course we cannot expect miracles,” says Simone Spuler, head of the Myology Lab at ECRC. “Sufferers who are in wheelchairs won’t just get up and start walking after the therapy. But for many patients, it is already a big step forward when a small muscle that is important for grasping or swallowing functions better again.”

Read the source article here.