A few weeks ago we held a Facebook Live “Ask the Stem Cell Team About Parkinson’s Disease” event. As you can imagine we got lots of questions but, because of time constraints, only had time to answer a few. Thanks to my fabulous CIRM colleagues, Dr. Lila Collins and Dr. Kent Fitzgerald, for putting together answers to some of the other questions. Here they are.

Q: It seems like we have been hearing for years that stem cells can help people with Parkinson’s, why is it taking so long?

A: Early experiments in Sweden using fetal tissue did provide a proof of concept for the strategy of replacing dopamine producing cells damaged or lost in Parkinson’s disease (PD) . At first, this seemed like we were on the cusp of a cell therapy cure for PD, however, we soon learned based on some side effects seen with this approach (in particular dyskinesias or uncontrollable muscle movements) that the solution was not as simple as once thought.

While this didn’t produce the answer it did provide some valuable lessons.

The importance of dopaminergic (DA) producing cell type and the location in the brain of the transplant. Simply placing the replacement cells in the brain is not enough. It was initially thought that the best site to place these DA cells is a region in the brain called the SN, because this area helps to regulate movement. However, this area also plays a role in learning, emotion and the brains reward system. This is effectively a complex wiring system that exists in a balance, “rewiring” it wrong can have unintended and significant side effects.

Another factor impacting progress has been understanding the importance of disease stage. If the disease is too advanced when cells are given then the transplant may no longer be able to provide benefit. This is because DA transplants replace the lost neurons we use to control movement, but other connected brain systems have atrophied in response to losing input from the lost neurons. There is a massive amount of work (involving large groups and including foundations like the Michael J Fox Foundation) seeking to identify PD early in the disease course where therapies have the best chance of showing an effect. Clinical trials will ultimately help to determine the best timing for treatment intervention.

Ideally, in addition to the cell therapies that would replace lost or damaged cells we also want to find a therapy that slows or stops the underlying biology causing progression of the disease.

So, I think we’re going to see more gene therapy trials including those targeting the small minority of PD that is driven by known mutations. In fact, Prevail Therapeutics will soon start a trial in patients with GBA1 mutations. Hopefully, replacing the enzyme in this type of genetic PD will prevent degeneration.

And, we are also seeing gene therapy approaches to address forms of PD that we don’t know the cause, including a trial to rescue sick neurons with GDNF which is a neurotrophic factor (which helps support the growth and survival of these brain cells) led by Dr Bankiewicz and trials by Axovant and Voyager, partnered with Neurocrine aimed at restoring dopamine generation in the brain.

A small news report came out earlier this year about a recently completed clinical trial by Roche Pharma and Prothena. This addressed the build up in the brain of what are called lewy bodies, a problem common to many forms of PD. While the official trial results aren’t published yet, a recent press release suggests reason for optimism. Apparently, the treatment failed to statistically improve the main clinical measurement, but other measured endpoints saw improvement and it’s possible an updated form of this treatment will be tested again in the hopes of seeing an improved effect.

Finally, I’d like to call attention to the G force trials. Gforce is a global collaborative effort to drive the field forward combining lessons learned from previous studies with best practices for cell replacement in PD. These first-in-human safety trials to replace the dopaminergic neurons (DANs) damaged by PD have shared design features including identifying what the best goals are and how to measure those.

The CIRA trial, Dr Jun Takahashi

The NYSTEM PD trial, Dr Lorenz Studer

The EUROSTEMPD trial, Dr Roger Barker.

And the Summit PD trial, Dr Jeanne Loring of Aspen Neuroscience.

Taken together these should tell us quite a lot about the best way to replace these critical neurons in PD.

As with any completely novel approach in medicine, much validation and safety work must be completed before becoming available to patients

The current approach (for cell replacement) has evolved significantly from those early studies to use cells engineered in the lab to be much more specialized and representing the types believed to have the best therapeutic effects with low probability of the side effects (dyskinesias) seen in earlier trials.

If we don’t really know the cause of Parkinson’s disease, how can we cure it or develop treatments to slow it down?

PD can now be divided into major categories including 1. Sporadic, 2. Familial.

For the sporadic cases, there are some hallmarks in the biology of the neurons affected in the disease that are common among patients. These can be things like oxidative stress (which damages cells), or clumps of proteins (like a-synuclein) that serve to block normal cell function and become toxic, killing the DA neurons.

The second class of “familial” cases all share one or more genetic changes that are believed to cause the disease. Mutations in genes (like GBA, LRRK2, PRKN, SNCA) make up around fifteen percent of the population affected, but the similarity in these gene mutations make them attractive targets for drug development.

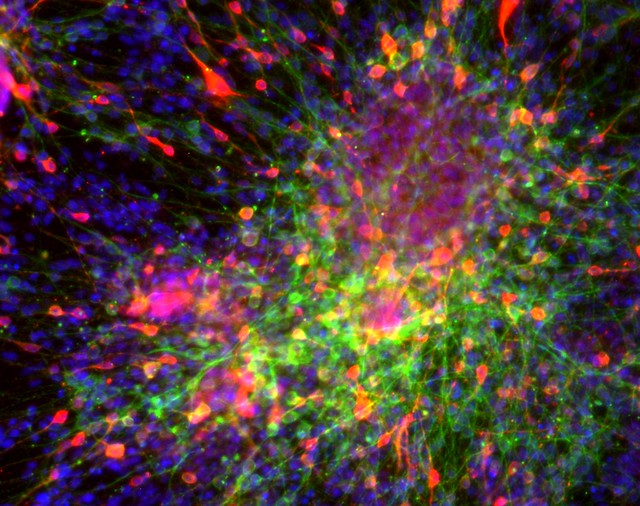

CIRM has funded projects to generate “disease in a dish” models using neurons made from adults with Parkinson’s disease. Stem cell-derived models like this have enabled not only a deep probing of the underlying biology in Parkinson’s, which has helped to identify new targets for investigation, but have also allowed for the testing of possible therapies in these cell-based systems.

iPSC-derived neurons are believed to be an excellent model for this type of work as they can possess known familial mutations but also show the rest of the patients genetic background which may also be a contributing factor to the development of PD. They therefore contain both known and unknown factors that can be tested for effective therapy development.

I have heard of scientists creating things called brain organoids, clumps of brain cells that can act a little bit like a brain. Can we use these to figure out what’s happening in the brain of people with Parkinson’s and to develop treatments?

There is considerable excitement about the use of brain organoids as a way of creating a model for the complex cell-to-cell interactions in the brain. Using these 3D organoid models may allow us to gain a better understanding of what happens inside the brain, and develop ways to treat issues like PD.

The organoids can contain multiple cell types including microglia which have been a hot topic of research in PD as they are responsible for cleaning up and maintaining the health of cells in the brain. CIRM has funded the Salk Institute’s Dr. Fred Gage’s to do work in this area.

If you go online you can find lots of stem cells clinics, all over the US, that claim they can use stem cells to help people with Parkinson’s. Should I go to them?

In a word, no! These clinics offer a wide variety of therapies using different kinds of cells or tissues (including the patient’s own blood or fat cells) but they have one thing in common; none of these therapies have been tested in a clinical trial to show they are even safe, let alone effective. These clinics also charge thousands, sometimes tens of thousands of dollars these therapies, and because it’s not covered by insurance this all comes out of the patient’s pocket.

These predatory clinics are peddling hope, but are unable to back it up with any proof it will work. They frequently have slick, well-designed websites, and “testimonials” from satisfied customers. But if they really had a treatment for Parkinson’s they wouldn’t be running clinics out of shopping malls they’d be operating huge medical centers because the worldwide need for an effective therapy is so great.

Here’s a link to the page on our website that can help you decide if a clinical trial or “therapy” is right for you.

Is it better to use your own cells turned into brain cells, or cells from a healthy donor?

This is the BIG question that nobody has evidence to provide an answer to. At least not yet.

Let’s start with the basics. Why would you want to use your own cells? The main answer is the immune system. Transplanted cells can really be viewed as similar to an organ (kidney, liver etc) transplant. As you likely know, when a patient receives an organ transplant the patient’s immune system will often recognize the tissue/organ as foreign and attack it. This can result in the body rejecting what is supposed to be a life-saving organ. This is why people receiving organ transplants are typically placed on immunosuppressive “anti-rejection “drugs to help stop this reaction.

In the case of transplanted dopamine producing neurons from a donor other than the patient, it’s likely that the immune system would eliminate these cells after a short while and this would stop any therapeutic benefit from the cells. A caveat to this is that the brain is a “somewhat” immune privileged organ which means that normal immune surveillance and rejection doesn’t always work the same way with the brain. In fact analysis of the brains collected from the first Swedish patients to receive fetal transplants showed (among other things) that several patients still had viable transplanted cells (persistence) in their brains.

Transplanting DA neurons made from the patient themselves (the iPSC method) would effectively remove this risk of the immune system attack as the cells would not be recognized as foreign.

CIRM previously funded a discovery project with Jeanne Loring from Scripps Research Institute that sought to generate DA neurons from Parkinson’s patients for use as a potential transplant therapy in these same patients. This project has since been taken on by a company formed, by Dr Loring, called Aspen Neuroscience. They hope to bring this potential therapy into clinical trials in the near future.

A commonly cited potential downside to this approach is that patients with genetic (familial) Parkinson’s would be receiving neurons generated with cells that may have the same mutations that caused the problem in the first place. However, as it can typically take decades to develop PD, these cells could likely function for a long time. and prove to be better than any current therapies.

Creating cells from each individual patient (called autologous) is likely to be very expensive and possibly even cost-prohibitive. That is why many researchers are working on developing an “off the shelf” therapy, one that uses cells from a donor (called allogeneic)would be available as and when it’s needed.

When the coronavirus happened, it seemed as if overnight the FDA was approving clinical trials for treatments for the virus. Why can’t it work that fast for Parkinson’s disease?

While we don’t know what will ultimately work for COVID-19, we know what the enemy looks like. We also have lots of experience treating viral infections and creating vaccines. The coronavirus has already been sequenced, so we are building upon our understanding of other viruses to select a course to interrupt it. In contrast, the field is still trying to understand the drivers of PD that would respond to therapeutic targeting and therefore, it’s not precisely clear how best to modify the course of neurodegenerative disease. So, in one sense, while it’s not as fast as we’d like it to be, the work on COVID-19 has a bit of a head start.

Much of the early work on COVID-19 therapies is also centered on re-purposing therapies that were previously in development. As a result, these potential treatments have a much easier time entering clinical trials as there is a lot known about them (such as how safe they are etc.). That said, there are many additional therapeutic strategies (some of which CIRM is funding) which are still far off from being tested in the clinic.

The concern of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is often centered on the safety of a proposed therapy. The less known, the more cautious they tend to be.

As you can imagine, transplanting cells into the brain of a PD patient creates a significant potential for problems and so the FDA needs to be cautious when approving clinical trials to ensure patient safety.