When Kurt Gillenberg was 10 months old, his parents knew something wasn’t right. But it wasn’t until he reached 18 months that they found a doctor at the University of California, San Diego, who diagnosed Kurt with cystinosis – a rare genetic, metabolic defect that impacts over 2,000 people worldwide and around 500-600 people in the United States.

Cystinosis is a genetic disease in which people fail to make a protein called cystinosin that transports the amino acid cystine around cells. Without cystinosin, cystine accumulates and forms crystals within the cells; damaging kidney, eyes, muscles and other organ tissues.

Although there are drugs to help reduce the levels of cystine in cells, there is currently no cure and people with the disease often don’t grow to their full height and die at an average of 28 years-old.

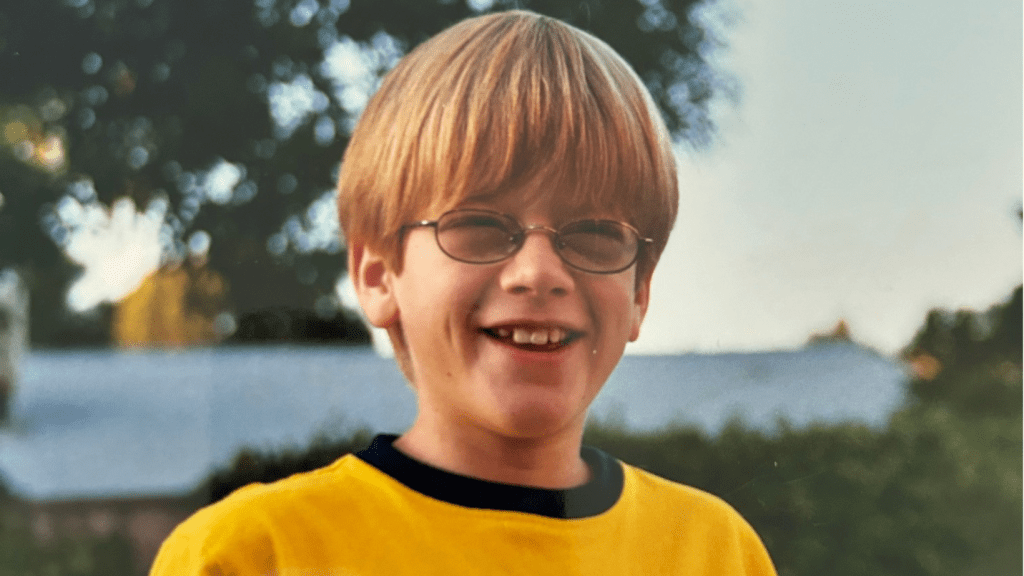

A hard childhood

“When I was first diagnosed, doctors told my parents that even though they could treat the disease, it would eventually kill me,” Kurt said.

At 32, he has had 18 surgeries, and his life has been disrupted with symptoms that include vomiting, diarrhea, fatigue, and extreme thirst. He has had multiple kidney transplants and is on medication to maintain those transplants.

He is now participating in a CIRM-funded clinical trial led by Stephanie Cherqui, PhD, professor of pediatrics at UC San Diego School of Medicine and chair of the Cystinosis Stem Cell and Gene Therapy Consortium.

“I learned a lot of life lessons young and usually the hard way,” Kurt said. “When living with a chronic disease, life tends to go on pause a lot. I learned a long time ago to try and live life to the fullest because you never know if one day soon, your life is going to have to hit that pause button again.”

The potential of stem cells and gene therapy

The therapy being tested involves collecting blood-forming stem cells from Kurt’s bone marrow and modifying the cystinosin gene within those cells to produce a healthy copy of the protein. The team then reintroduced those modified stem cells into his bone marrow, where they proliferate, or multiply, and produce blood cells that can deliver the cystosin protein throughout the body.

If successful, the cystosin from the blood cells will infuse into cells of the body and reduce accumulation of cystine. The approach has been successful in animal studies, and now the clinical trial has shown the treatment to be effective in people, including Kurt.

The approach is not without risks. Before reintroducing the modified blood-forming stem cells patients go through chemotherapy to destroy existing stem cells in the bone marrow. This clears space for the modified cells to take hold and multiply. That chemotherapy causes temporary side effects including a decreased immune system, weakness, nausea, and other symptoms.

To Kurt, the challenges were worth it for two reasons. “First thing was that just the possibility of being cured by this new type of procedure was too good of a chance to pass up,” he said. “To think that I could live the rest of my life without fear of dying before my time and to not have to take that horrible medication ever again. The second reason was that I wanted to do it for all present and future cystinosis patients.”

Hope for patients with cystinosis

After participating in the trial, Kurt is feeling much better. “I have been able to do things I never would have thought possible just a few years ago,” he said. “My energy has increased. I have never been stronger and one thing I noticed after transplant is my strength and stamina in the gym increased dramatically.”

This trial is one of many CIRM is supporting to help find treatments for rare diseases. Major pharmaceutical companies often overlook these diseases because of the lack of potential revenue, leaving people who have those diseases with little hope.

“I really appreciate the charities and individuals who raise money to fund research for diseases like Cystinosis. Without whom, trials like these would not be possible,” stated Kurt.

“This approach may provide a one-time, lifelong therapy that may prevent the need for kidney transplantation and long-term complications caused by cystine buildup,” Dr. Cherqui said.

“CIRM played a significant role in advancing the stem cell gene therapy program for cystinosis from bed-to-bedside. Through its funding and support, CIRM has allowed me to perform the pre-clinical studies required for an investigational new drug application and then to conduct the first phase of the clinical trial in an academic setting.”

It’s the thought of helping people like Kurt that keeps us going at CIRM. For people with cystinosis, it brings a renewed sense of hope and possibility.

Watch a video featuring Dr. Cherqui and another patient in the trial, Jordan Janz, talking about the therapy.

Written by guest contributor Amy Adams

please can you advise me do you treat fabrys disease? It’s really effecting my life. My father and his brother both died young of fabrys disease.